Is a priori knowledge really possible? Is there a distinction between a priori and a posteriori? What are priori propositions?

The Latin terms a priori and a posteriori mean ‘from what is before’ and ‘from what is after,’ respectively. A type of justification (say, via perception) is fallible if and onlyif it is possible to be justified in that way in holding a falsebelief. Just as we can be empirically justified in believing a falseproposition (e.g., 9b: two quarts of water plus two quarts of carbon tetrachloride do notcombine to yield four quarts of liquid), philosophers argue that wecan also be a priori justified in believing a falseproposition.

Perhaps Kant was a priori justified in believingthat every event has a cause. He thought that the proposition had thatstatus. Yet many physicists believe that there are genuinely randomevents at the subatomic level, a. See full list on plato.

A standard answer to the question about the difference between apriori and empirical justification is that a priorijustification is independent of experience and empirical justificationis not, and this seems to explain the contrasts present in the fifteenexamples above. But various things have been meant by“experience”. On a narrow account,“experience” refers to sense experience, that is, toexperiences that come from the use of our five senses: sight, touch,hearing, smell, and taste. Malmgren notes thatthere are several different ways to characterize intuitive judgments,but because they are all controversial, she characterizes them byreference to examples.

For her, “an intuitive judgment is anyjudgment relevan. One way to answer the question about the nature of a priorijustification and knowledge is to adopt a bottom up approach. Startwith contrasting examples like the fifteen above and construct atheory that explains the difference. We have seen that Bealer thinks that a rational intuition is a modalseeming: either a seeming to be true and necessarily true, or aseeming to be possible.

This definition of an apriori intuition allows us to distinguish between what Bealercalled a physical intuition that a house undermined. A new branch of philosophy called experimental philosophy (X-phi forshort) has studied the intuitive judgments of people (oftenstudents) when presented with well-known examples in epistemology andethics. They ask these people (often from different ethnic, cultural,economic, and educational backgrounds) whether someone in ahypothetical scenario knows, or only believes, that some propositionis true, say, in Sheep whether the person knows, or onlybelieves, that there are sheep in the field. Can intuitions be checked for accuracy? Suppose, for the sake of argument, we grant that intuitionsproperly understood and had under ideal conditions by people witha deep understanding of the relevant concepts can justify certainpropositions.

But can they yield knowledge about the externalworld? Carrie Jenkins has argued that they can insofar as theconcepts that play a role in a priori justification have beenshaped by experience. She thinks that for knowledge (notjustification) our concepts must be grounded. By this shemeans that they must accurately and non-accidentally represent theworld.

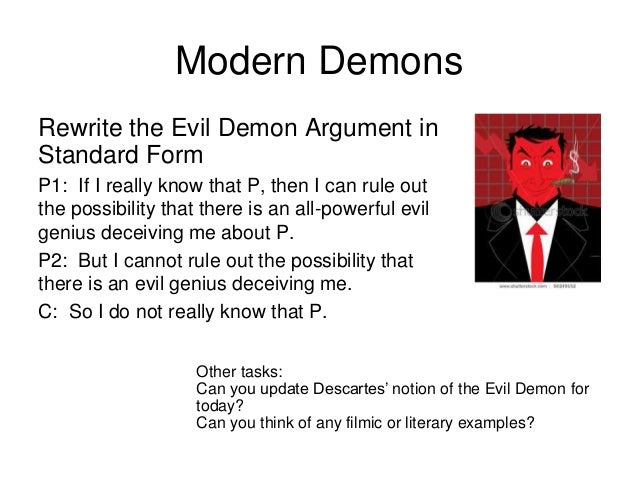

So a BIV can have a justifie though not a grounde. It is widely, though not universally, held that knowledge is partlyanalyzable in terms of justified true belief. But, as we’veseen, Gettier examples show that having a justified true belief is notsufficient for knowledge. We need some anti-luck condition in additionto JTB to rule out cases where there is a JTB but not knowledgebecause, in some sense, the person in the Gettier situation is luckyto have a true belief given the way his evidence is related to thetruth of his belief. The Lottery Paradox suggests that even more than JTB and an anti-luckcondition are required for knowledge.

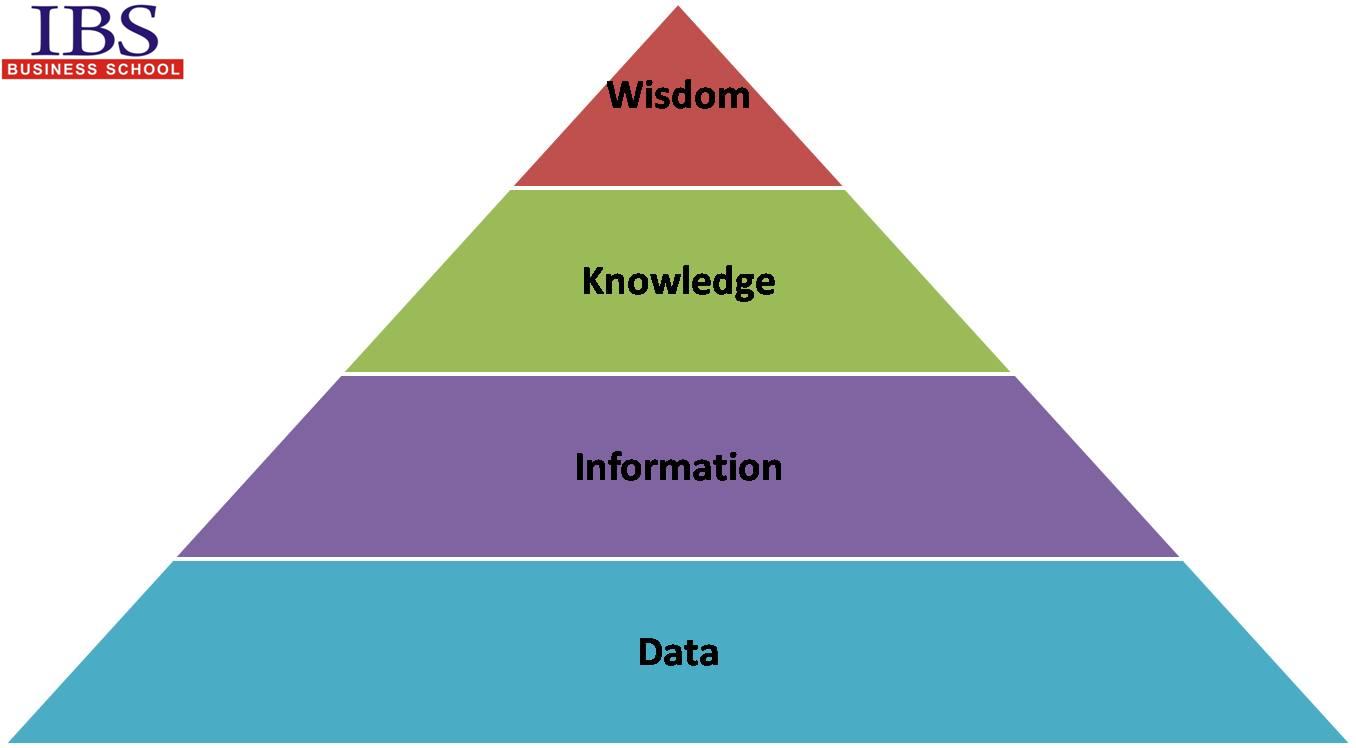

The chances that you hold thewinning ticket in a one million ticket lottery is one in a million,and that you hold a losing ticket, 999in a million. Suppose youknow what the probability of your holding a losing ticket is and thatyou in fact have a losing ticket. Then you seem to have a justifiedbelief that your ticket is a loser (because you know that’s verylikely true), and it is true that it is a. The distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge thus broadly corresponds to the distinction between empirical and nonempirical knowledge. By this account, a proposition is analytic if the predicate concept of the proposition is contained within the subject concept.

The claim that all bachelors are unmar. A necessary proposition is one the truth value of which remains constant across all possible worlds. Thus a necessarily true proposition is one that is true in every possible worl and a necessarily false proposition is one that is false in every possible world. By contrast, the truth value of contingent propositions is not fixed across all possible worlds: for any contingent proposition, there is at least one possible world in which it is true and at least one possible world in which it is. In Section above, it was noted that a posteriori justification is said to derive from experience and a priori justification to be independent of experience.

To further clarify this distinction, more must be said about the relevant sense of “experience”. There is no widely accepted specific characterization of the kind of experience in question. Philosophers instead have had more to say about how not to characterize it.

There is broad agreement, for instance, that experience should not be equ. It is also important to examine in more detail the way in which a priori justification is thought to be independent of experience. Here again the standard characterizations are typically negative. There are at least two ways in which a priori justification is often said not to be independent of experience.

The first begins with the observation that before one can be a priori justified in believing a given claim, one must understand that claim. The reasoning for this is that for many a priori c. More needs to be sai however, about the positive characterization, both because as it stands it remains less epistemically illuminating than it might and because it is not the only positive characterization available. How, then, might reason or rational reflection by itself lead a person to think that a part.

Self-Evidence,” Philosophical Perspectives, vol. Tomberlin (Oxford: Blackwell), pp. The A Priori,” in Language, Truth and Logic, 2nd ed. New York: Dover), pp.

John Greco and Ernest Sosa (Oxford: Blackwell), pp. A Priori is a philosophical term that is used in several different ways. The term is suppose to mean knowledge that is gained through deduction, and not through empirical evidence. For instance, if I have two apples now, and I plan to add three apples, I will have five apples. This is knowledge gained deductively.

Some have argued that the very idea of a god is an a priori concept because most people at least have not had any direct experience of any gods (some claim to have, but those claims cannot be tested). Since at least the 17th century, a sharp distinction has been drawn between a priori knowledge and a posteriori knowledge. Knowledge or arguments based on experience or empirical evidence. The Latin phase a priori can be translated from what comes before and a posteriori means from what comes later.

A priori and a posteriori knowledge. Examples of a priori knowledge. Mathematical equations, for example, are an example of a priori knowledge , since they do not require any real-world evidence to be considered true. You might argue that all knowledge is based in real-world experience. If you know how many re white, and blue gum balls are in the gum ball machine, this a priori knowledge can help you predict the color of the next ones to be dispensed.

In the term’s most basic use, a person could assume that, if Bobby went to Kindergarten at least six days, he went to Kindergarten more than five days. Check out this great listen on Audible. Since the ability to reason presupposes knowledge of dependence-relations, it follows that people are ab initio able to r. In his opening argument, the student mentioned nothing beyond his a priori knowledge. English dictionary definition of a priori. A posteriori knowledge is often compared to a priori knowledge , which is knowledge that is known to be true based on reason alone.

Compared to a priori knowledge , such as a mathematical equation, a posteriori knowledge is more likely to be false, since it relys on an interpretation of an experience.